Sprint Commitment: There’s No Guarantee

We corrupt the intent of the Sprint commitment when we use it as a beating stick for teams that fail to complete the Sprint Backlog.

Sprint Commitment Origins

For as long as I’ve known about Scrum, I’ve been aware of the “Sprint Commitment.” One of the first books I read on my agile journey was Kenneth Rubin’s Essential Scrum: A Practical Guide to the Most Popular Agile Process. The following quote is from the Sprint Planning chapter:

Quote

“At the completion of sprint planning the development team finalizes its commitment to the business value it will deliver by the end of the sprint. The sprint goal and the selected product backlog items embody that commitment.”

Kenneth S. Rubin in Essential Scrum

Yet, even reviewing the earliest version of the Scrum Guide, I’m unable to find a reference to a Sprint Commitment that could legitimately be the source for this final step in Sprint Planning.

I started to suspect this was another example of the Mandela Effect at play.

A google search on “Sprint Commitment” will bring up articles similar to this one, all implying that this step is a misinterpretation of the Scrum Guide. Additionally, I can clearly remember two different leaders from two companies directing me to confirm Scrum Team’s commitment to the Sprint Backlog. The context of these conversations was that punishment awaited the team if they missed their “Sprint Commitment.” So I’m not the only one who believes this to be a defined step in Sprint Planning.

Further sleuthing led me to Gunther Verheyen’s paper on Scrum, reminding me that the evolution of Scrum started before the publication of the first Scrum Guide.

Ken Schwaber’s OOPSLA paper “SCRUM Development Process” does not refer to the terms commit or commitment; but the 1999 paper “SCRUM: An extension pattern language for hyperproductive software development” does.

Quote

“Each Sprint takes a pre-allocated amount of work from the Backlog. The team commits to it. As a rule nothing is added externally during a sprint. External additions are added to the global backlog. Issues resulting from the Sprint can also be added to the Backlog. A Sprint ends with a Demonstration of new functionality.”

If you were to focus only on the first two sentences, and you perhaps come from a traditional command and control background, I could see how one might conclude that the team is supposed to guarantee the delivery of the Sprint Backlog.

However, taking the additional context of the paragraph into account, I believe the intent of the commitment is clearly to prevent what traditional project management would refer to as scope creep. “As a rule, nothing is added externally during a sprint,” as in stakeholders and management cannot force new things onto the list while the team is executing the Sprint.

Additional proof that this might be the intention of the authors comes in a later passage:

Quote

“Some problems are “wicked”, that is it difficult to even describe the problem without a notion of the solution. It is wrong to expect developers do to a clean design and commit to it at the start of this kind of problems. Experimentation, feedback, creativity are needed.”

Again, the authors use the term commit here in the context of locking down the plan. As we all know, the existence of a plan doesn’t guarantee its flawless execution.

Before we go down the rabbit hole of all the Scrum literature, let’s take a step back and find our old friend, the dictionary, to ensure that we understand the words commit and commitment.

Definitions Commit and Commitment

According to The Oxford English Dictionary, to commit is to “pledge or bind (a person or an organization) to a certain course or policy.”

In our context, the course of action is the Sprint Plan.

Commitment has two definitions, both of which are applicable in this context.

The second definition is “an engagement or obligation that restricts freedom of action.” When a team is committed to the Sprint Backlog, they agree to focus on that work and not be interrupted by other additional stakeholder requests.

Commitment’s first definition is “the state or quality of being dedicated to a cause, activity, etc.” When I indicate my dedication to fighting world hunger, that doesn’t imply that I’m guaranteeing to solve the problem in two weeks. It means that it’s something I care about, and I’m willing to do what’s within my power to make a difference.

In a 2016 letter to stakeholders, Jeff Bezos talked about the Amazon leadership principle of “disagree and commit.”

Quote

“We recently greenlit a particular Amazon Studios original. I told the team my view: debatable whether it would be interesting enough, complicated to produce, the business terms aren’t that good, and we have lots of other opportunities. They had a completely different opinion and wanted to go ahead. I wrote back right away with - I disagree and commit and hope it becomes the most watched thing we’ve ever made.”

Jeff Bezos

Nowhere does he imply by his commitment that he’s guaranteeing that this Amazon Studios original will be the most-watched thing ever made. In fact, it’s much the opposite. He’s admitting that he doesn’t know what the future will be and indicating that he will not be a roadblock to the show’s potential success.

Scrum Guide Revisions

If you still have doubts about the Scrum Guide’s intentions for committing and commitment, I invite you to look at the revisions to these terms over time.

In 2011, the authors removed all references to commit and added clarity to the Sprint Planning section to call out that the team was creating a forecast.

In 2016, the revisions added the Scrum values. Commitment, being one of the five, is described as “People personally commit to achieving the goals of the Scrum Team.”

In 2020, the description of the Scrum value changed to “The Scrum Team commits to achieving its goals and to supporting each other.”

This change elucidated that the commitment was more of an internal team agreement. This agreement harkens back to collective ownership. For me, this invariably brings to mind the three musketeers. All for one and one for all.

Also, in 2020, each artifact received a commitment:

Quote

“Each artifact contains a commitment to ensure it provides information that enhances transparency and focus against which progress can be measured:

For the Product Backlog it is the Product Goal.

For the Sprint Backlog it is the Sprint Goal.

For the Increment it is the Definition of Done.

These commitments exist to reinforce empiricism and the Scrum values for the Scrum Team and their stakeholders.”

Scrum Guide

They further establish that the purpose behind a commitment has more to do with setting a focus than making a guarantee.

Why We Can’t Guarantee Our Work

Imagine that I ask you to provide me with an estimate to clean out my husband’s car. He drives a 2007 Chevy Cobalt. I can tell you that you’re likely to find some fast food bags, way too many empty water bottles, and an annoying amount of dog hair from the last time our daughter borrowed the car.

Now that you’ve provided that estimate, I will hold you to that. Would you like to change that estimate? Okay, now that we have a final estimate, be aware that I expect that you’ve guaranteed that estimate.

Unfortunately, even though you’re an expert car detailer, you forgot to ask if there was a dead body in the trunk. You discover this only after you’ve already cleaned most of the interior. Like any other good citizen, you call the cops to report the corpse. The police immediately arrest my husband and impound the vehicle.

But don’t think that gets you off the hook for that guarantee. I still want you to get the car detailed within your estimated time. I don’t care that the police have the vehicle, and I don’t care that it’s out of your control when or if they’ll ever release the car. These all sound like excuses to me. You’re the expert; figure out how to do what you said you’d do.

This example is very contrived, but Scrum Teams continually run into this type of situation. There’s a tendency for stakeholders to forget that estimates are just guesses. We’d all like to live in a world where everything can be predicted and planned perfectly upfront, but the truth is, we’re going to discover things about the work that we had no way of knowing up front. Those discoveries will impact the timelines.

If you think I’m just being a pushover Scrum Master, take the Scrum Guide’s opinion on it:

Quote

“As the Developers work during the Sprint, they keep the Sprint Goal in mind. If the work turns out to be different than they expected, they collaborate with the Product Owner to negotiate the scope of the Sprint Backlog within the Sprint without affecting the Sprint Goal.”

Scrum Guide

If the Sprint Backlog was a guarantee from the Scrum Team to stakeholders, why would there be a call out for scope negotiation based on what we learn in the Sprint?

What Is Sprint Commitment

Sprint commitment refers to the team’s agreement to complete the items on the Sprint Backlog within the sprint. However, it’s important to note that the sprint backlog is a forecast, not a guarantee. While the team commits to completing the items, unexpected issues may arise, and adjustments may need to be made during the sprint.

Sustainable Pace

When we constantly push a team to work more and more hours to meet unrealistic Sprint Goals, the side effects are destabilizing. Collaboration suffers as the team frays from the stress, quality decreases as we cut more and more corners, and productivity declines without ample rest. Eventually, this leads to burnout and increased turnover. With fewer members on the team, the pressure increases for those that remain.

Quote

“Agile processes promote sustainable development. The sponsors, developers, and users should be able to maintain a constant pace indefinitely.”

Agile Manifesto

You might wonder, if the Scrum Team controls the selected work for a Sprint, and they know that they worked at an unsustainable pace last Sprint, why don’t they bring in less work next Sprint? This course of action is appropriate, yet we rarely choose it in practice.

A dysfunction that arises from tracking velocity is that we constantly look for ways to improve it. On the surface, that seems like a good idea, but the thing that most teams forget is that everyone has a top speed.

Although continuous improvement is a goal of any agile approach, we should not expect a team’s throughput to grow exponentially. Reaching a consistent pace should not be viewed as a failure; it should be a sign of success. The more constant we are, the more predictable we are.

Who Is Responsible for Sprint Commitments

In Scrum, the Sprint Goal is the closest thing to a Sprint Commitment. The Development Team is responsible for meeting this goal and can negotiate the scope of the Sprint Backlog with the Product Owner. The Scrum Master helps remove impediments.

Though sustainable pace is a consideration, it isn’t a free ticket to a laid-back existence. We need to take the Sprint Backlog seriously.

It is called a Sprint and not a meander. We need to be committed to the process and our other team members and do what we can within reasonable limits to accomplish the goal we established in Sprint Planning, but we don’t need to kill ourselves doing it.

Acknowledge the Unfinished Sprint Backlog

As soon as we recognize that we’re not going to be able to complete the Sprint Backlog, we need to let the Product Owner know. The Sprint Goal itself is still valid, and we need to discuss options for reducing the scope of the Sprint while still accomplishing the essence of the Sprint Goal.

So, we’ve done everything in our power, but we still couldn’t finish the Sprint Backlog. What now?

There will be times when this happens. In fact, Mike Cohn suggests that we’re doing good if we finish 100% of the work 80% of the time. Completing all of the work all of the time might be a sign that we’re phoning it in and not challenging ourselves.

We should discuss unfinished items as a team. When possible, we want to get to the root cause and determine if there are any process improvements we can make to prevent the same issue from happening in the future. The Sprint Retrospective can be an excellent time to have these discussions.

Stakeholder Response to an Unfinished Sprint Backlog

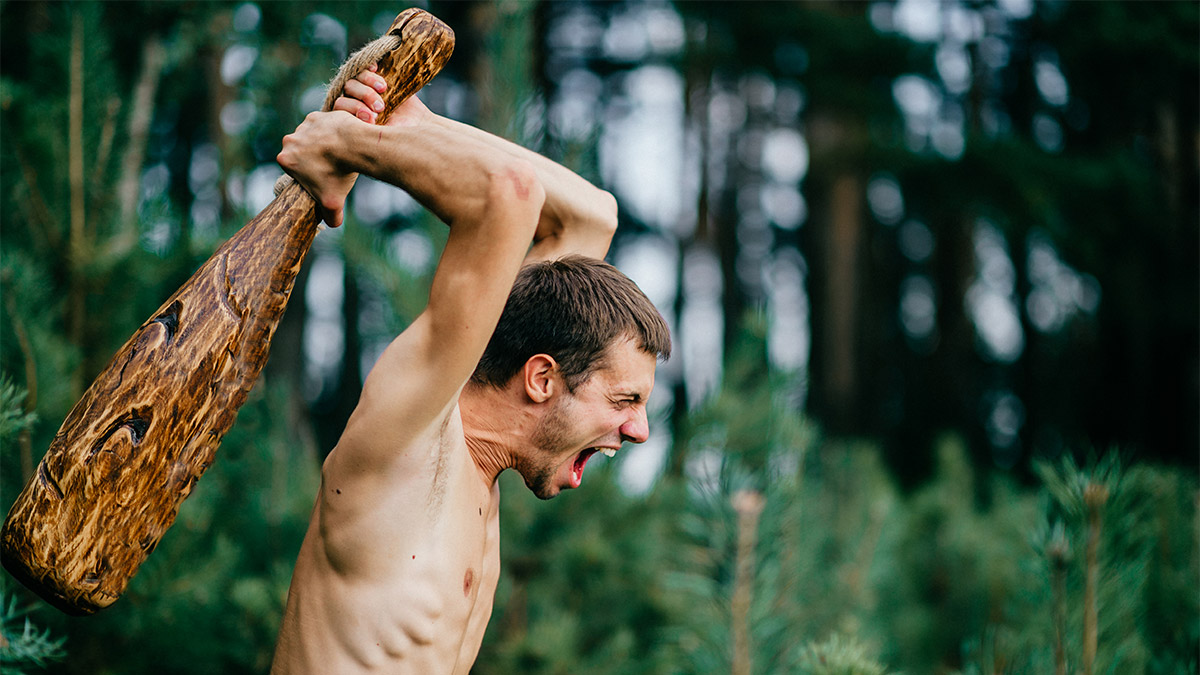

If your stakeholders enter the Sprint Review like Negan from The Walking Dead - just looking to make an example out of someone, you might have a dysfunctional team.

It simply doesn’t make sense to punish people for their lack of omniscience.

In a healthy culture, stakeholders will accept that people are trying their best and are continuously looking for ways to improve the process.

If your stakeholders choose not to accept reality after coaching and attempting to set realistic expectations, don’t worry about it so much.

As professionals, all we can do is be transparent about the situation and continue to set realistic expectations. We cannot force our stakeholders to subscribe to reality.

Works Consulted

- Essential Scrum: A Practical Guide to the Most Popular Agile Process | Kenneth S. Rubin | Addison-Wesley Professional, 2012.

- The Self-Abuse of Sprint Commitment | agileconnection.com | Accessed 22 Apr. 2023.

- Why Plans Fail: Cognitive Bias, Decision Making, and Your Business | Jim Benson | Modus Cooperandi Press, 2011.

- Commitment vs. Forecast: A Subtle But Important Change to Scrum | scrum.org | Accessed 22 Apr. 2023.

- Scrum Guide 2020 Update - Commitments | scrum.org | Accessed 22 Apr. 2023.

- Agile Manifesto | agilemanifesto.org | Accessed 22 Apr. 2023.

- Official Scrum Guide (Current and Past Versions) | mitchlacey.com | Accessed 22 Apr. 2023.

- Scrum Myth: The Sprint Backlog is a Commitment | scrum.org | Accessed 22 Apr. 2023.

- Scrum A Brief History of a Long-Lived Hype | guntherverheyen.com | Accessed 22 Apr. 2023.

- SCRUM Development Process | jeffsutherland.org | Accessed 22 Apr. 2023.

- SCRUM: An extension pattern language for hyperproductive software development | jeffsutherland.org | Accessed 22 Apr. 2023.

- Amazon 2016 Letter to Shareholders | aboutamazon.com | Accessed 22 Apr. 2023.

- Scrum Guide | scrumguides.org| Accessed 22 Apr. 2023.

TLDR

The Scrum literature has long since transitioned away from any language that would lead to stakeholders interpreting the Sprint Commitment as a guarantee. Those that are still clubbing teams over the head for partially completed Sprint Backlogs are doing psychological harm to the team. Enforcing unrealistic estimates leads to burnout, decreased quality, and increased turnover. The undesirable changes in these metrics reduce predictability. Process improvement is needed to increase predictability, not commitment and accountability.